We expect monogamous relationships to make us sexually happy for the rest of our lives. Here’s why we are wrong.

The world we live in was largely built by men for men. Many structures around us reflect male views, priorities, needs, and abilities. For centuries, even millennia, these structures “worked” because they only had to work for men. And male societies didn’t bother to ask women. The rise of feminism questions this lop-sided civilization that was designed around what men needed and wanted. That’s a good thing because it’s about damn time. But with progressing gender justice and women stepping into that male world, we notice that some things don’t work as they did for ages.

For example, the monogamous, sexually exclusive long-term relationship.

It came into being when people started to live in sedentary settlements, and private property was assigned to men. A form of relationship was needed to secure male wealth for following generations (patrilineal heritage) and to reduce social tension due to sexual competition among men. The first purpose is widely accepted among anthropologists and sociologists, the latter not so much. But getting rid of social tensions was a major challenge when people began to live together in the same place permanently. So giving men easy access to regular sex (as opposed to the female choice mating system) was an important purpose of a monogamous relationship. Women, however, weren’t asked about consent: they were forcibly married by their fathers, and marital sex was considered their duty.

Fortunately, that changed over the last five or six decades, but our ideas of relationship sex are still biased by male views. Time to clean up this mess.

(Note that — as always — I’m referring to principles, patterns, and trends, not individuals. Your experiences can differ from that patterns, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no pattern. Thanks.)

The bird and the fish

Imagine a bird and a fish that decide to live together. Whatever habitat they move in together, one of them will be a mismatch. The environment will not provide the necessary circumstances for them to thrive. Neither can the bird breathe underwater, nor can the fish walk (let alone fly) on land.

Now imagine the fish suddenly deciding where he wants to live. And he makes the bird live underwater.

The bird, of course, isn’t happy. It has to emerge regularly to breathe, it can’t use its flight muscles underwater, so they shrivel, and it has to endure many limitations to live with the fish.

It’s getting worse when the bird discovers the world above the water’s surface. It occurs to the little bird that something’s wrong. But the fish won’t admit that because it (or he) doesn’t want to lose the bird as its mate. So it tells the bird, “Why aren’t you like me? I have no trouble breathing underwater. There must be something wrong with you. Go, see a doctor.”

The doctor, also a fish, agrees and concludes that the bird suffers from a disease called AAD or avian aquatic dysfunction. The bird talks to specialists (all fish), takes swimming lessons, and learns breathing techniques, but things remain complicated, and both birds and fish are very sad. They want to be together, but some things just don’t add up.

I don’t wanna overstretch this analogy, I guess you get the point. Bird and fish lived together in a way that would never work, no matter how hard fish tries to force bird into thinking that’s its fault and they only need to change their aquatic skills to make it work.

Heterosexual men and women are just like birds and fish regarding their sexuality.

Same but different

Of course, men and women, the two most common genders, aren’t different species. Both are social creatures, both need physical touch to remain healthy, and both experience an endorphin rush through sexual interaction. But that doesn’t mean they can live a sexually fulfilling long-term relationship. Because biology. Sexual desire is linked to sex hormones.

The levels of male hormones, or androgens, remain relatively constant throughout the month. They only slightly fluctuate around a pretty stable level, and thus, the libido of physically and mentally healthy men is more or less the same every day. That brings us back to a world built by men for men because men brought their constant sex drive to the monogamous relationship when they created it.

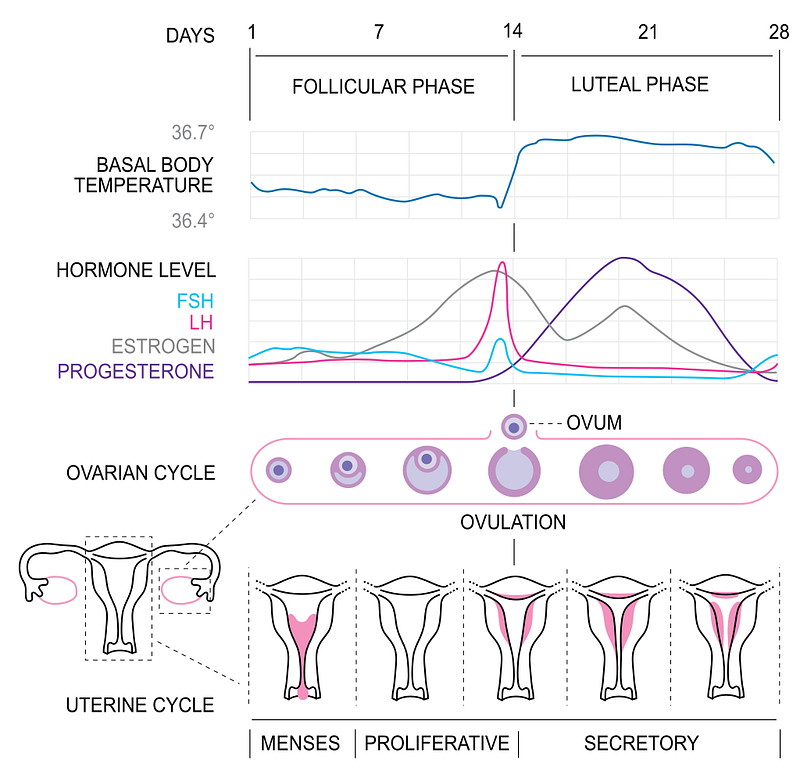

By Isometrik under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Conversely, female sex hormones fluctuate very strongly throughout the monthly cycle. The two most important hormones are estrogen and progesterone. The cycle starts on the first day of the period with low estrogen.

The estrogen levels then rise continuously and are highest during ovulation.

Immediately after that, the estrogen drops, and instead, progesterone is released until the period. In addition to this up and down, there are two more major hormones, the luteinizing hormone, and the follicle-stimulating hormone, both play an important role in inducing ovulation.

All this leads to a much more volatile libido in women, with it being strongest around ovulation and lowest shortly before and during the period.

Women who are very sensitive to their own hormone levels might be interested in sex only a couple of days per month. In other mammal species, these days are called heat or estrus. It’s a common misconception that the female sex drive, in general, is lower than the male. It’s not. It rather sways throughout the month, from “not interested in sex at all” to “I need it seven times a day”.

But there’s more. Not only does female sexuality swing all over the place, but it also has an expiration date after one full reproduction cycle. The reproduction cycle of mammals lasts from mating to weaning the offspring. So when the young are independent enough to feed on their own, the mother becomes fertile again and mates again — typically with a new partner. The human reproduction cycle is about four years long.

So, relying on physical touch to thrive and procreate doesn’t mean all genders developed the same kind of sexuality. It’s unfortunate, it’s frustrating, but it’s what Evolution thought was best. The described mating system with constant male sex drive and fluctuating female sex drive is called female choice (you might want to take a look at the summary of my book Female Choice — On the Rise and Fall of the Male Civilization since the book is not available in English).

A fish’s perspective

That brings us back to our friends, fish, and bird. Two main genders with different sexuality live together in a habitat that was designed by only one of them. It’s easy to see that a relationship model that doesn’t pay tribute to sexuality differences between the genders favors male sexuality. As long as women were considered disenfranchised property of men, the question of whether such a relationship model suits female libido was neglectable. Nobody cared whether they wanted or not, and they had no legal right to say no.

Today, women are more aware of their own needs, consent is an important topic, and marital rape is an official crime (at least here in Germany). And now that relationship sex is no longer a duty but a matter of consent of both partners, more and more couples in long-term relationships experience sexual frustration. Who would’ve thought that women who are free to say no actually make use of that right?

The two most common sexual problems in relationships are:

1. The man simply wants more sex throughout the month.

Both problems match the biology of female sexuality in an almost painful way. They’re exactly what you’d expect when women have the freedom to say no to relationship sex.

Now don’t get me wrong: the right of bodily autonomy must never be stripped from women. It’s the most important accomplishment of feminism, and I hope civilization will never fall back to that handmaid’s tale-ish purpose of women to sexually relieve and conceive.

With that being said, this could and should be the point where we start discussing sexually exclusive relationships as a structure that is more likely to make both partners sexually unhappy instead of happy in the long run. But remember: fish, I mean men created the structures of the sedentary civilization, and everything male was deemed normal, healthy, and good.

Every deviation from the male pattern was considered deficient. So instead of encouraging women to discover and embrace their sexuality rhythm, instead of telling them that they’re perfectly normal and healthy, we make them believe that there’s something wrong with them for not being open to intercourse every day of the month.

And they do believe. I recently talked to a gynecologist at a panel about “libido disorders” in women. He told me that many patients seek his help because their lack of desire for their partner causes relationship stress. He said he always asks the women who are bothered by the lack of sexual intercourse, and their first answer is always “Both of us”. But after digging a little deeper, they often change their answer to “My partner”.

The differences between willing, wanting & giving in

During the 1960s, American zoologist Desmond Morris stated that human female sexuality differs from most other animal species in that the woman is willing to engage in sexual intercourse every day of the month, regardless of whether she’s fertile. Most of his fellow science dudes agreed and even built evolutionary hypotheses about the origin of monogamy on that statement (see “concealed ovulation”, another myth of male science). Even today, the claim of so-called extended female sexuality is widely accepted. And false.

Let’s get back to animals, this time orangutans. Female orangutans also engage in mating when they’re not fertile. Especially when they come across a non-territorial or unflanged male. These males lack the impressive cheek pads of large dominant territory owners and are pretty much unattractive to females.

So they harass the females to the point where they simply coerce copulation, or the female gives in to avoid injury. A similar pattern was observed in captivity. But when the researchers changed the cage design so that the female could avoid contact with males, they actually did. They stayed by themselves, blissfully unbothered by the male’s desire, and only allowed males to approach or even initiated sex on their own when they were fertile.

Orangutan females are a perfect demonstration to show that giving in to pressure is not the same as being willing. Now you might say that not all human men are forcing their female partners into sex, and rightfully so. But try to think of force and pressure in a more abstract, less physical way.

In the dawn of the sedentary civilization, girls as young as twelve were forced into a sexual relationship with a man their father chose and who the girls (most probably) didn’t desire. The force applied to these girls and young women was quite literal. Nowadays, women in Western culture aren’t forced by law or tradition. But the expectation of the woman to be sexually approachable for her male partner is still strong.

When we make women believe that they are deficient and they have a “female sexual dysfunction” for not wanting sex with their partner, we are, in fact, applying pressure on them.

When we send women to see therapists and gynecologists to “fix” their sex drive because we see it as broken, we are, in fact, using force on them.

When we feed women androgens, male hormones, to boost their sex drive and please their male partner as they’re supposed to do, we are, in fact, pushing them to have more sex.

That pressure can lead to the somewhat awkward situation that even though partnered women are reporting a steep decrease in sexual desire for their partner over time, the reported frequency of sex doesn’t decrease at the same rate.

This basically means that women have sex with their partner even though they don’t desire him (anymore). And since lack of sexual desire is directly linked to sexual satisfaction, these women are spending their lives having sex they don’t really enjoy with men who they don’t really want. The willing wife, Morris stated, is rather a sexually neutral (can be convinced to have sex) wife.

Why can’t we just step back a little and accept that sexually exclusive relationships aren’t the only, let alone the best way to live together? Why can’t we see that allowing women and men to seek out sexual satisfaction outside of the relationship is a good thing? Why are we still expecting monogamous relationships to be forever sexually fulfilling, even though statistics tell us otherwise?

Isn’t it unfair to make women have sex even if they don’t want to? Isn’t it unfair to expect men to stay true to their female partner even though she doesn’t want them anymore?

The system of monogamous relationships doesn’t work in a world where women are free to say no. In my opinion, it’s more than time to accept the fact that male and female sexuality show different rhythms and, therefore, probably will never work in a system designed for only one of them.

Set yourself and your partner free by taking the responsibility for your sexual pleasure from their shoulders.

Hm, jetzt müssen die Vögel nur noch erkennen dass sie keine Fische sind. Und beide zusammen die gesellschaftlichen Rahmenbedingungen ändern.

Eine Frage hätte ich in dem Zusammenhang noch, wie sieht es mit den evolutionären Ursachen der Eifersucht aus, gibt es die oder ist Eifersucht eher ein soziologisches Thema?

Dein Englisch ist bewundernswert gut, aber der Grund, warum du diesen Text in Englisch verfasst hast, ist mir nicht ersichtlich. In der Sache überzeugen mich deine Ausführungen in jeder Hinsicht – außer, was die Lösung der Probleme betrifft, die durch die unterschiedlichen, biologisch verursachten Rhythmen männlicher und weiblicher Sexualität entstehen. Eine Gesellschaft, in der das Modell der sexuell offenen Partnerschaft (jeder befriedigt seine Wünsche nicht nur innerhalb der Partnerschaft, sondern auch außerhalb) in nennenswertem Ausmaß praktiziert wird, ist momentan nicht mal am Horizont erkennbar. Wenn überhaupt, wird sie nach meinem Gefühl vielleicht in tausend Jahren kommen. Und der Grund dafür ist, siehe Patriks Frage, die Eifersucht bzw. die Treue-Forderung. Übrigens findet man zu den evolutionären Ursachen der Eifersucht sehr leicht Literatur im Internet.

Ich sehe da eine verblüffende Parallele zur Klimaänderung. Die Sache selbst, die Fakten, sind mittlerweile hinreichend bekannt und werden nur von Minderheiten angezweifelt. Das Gleiche gilt für die Differenzen zwischen Mann und Frau, was die Lust auf Sex angeht (ich kann allerdings nur für die Bildungsschicht, in der ich lebe, und für Leute über 50 sprechen). Aber sich zu ändern, also beim Klima den gewohnten Lebensstil einzuschränken (weniger Autofahren, keine Fernreisen usw.) und beim Sex das Treuegebot aufzuweichen und dem Partner “Untreue” zu erlauben, fällt den Leuten wahnsinnig schwer. Ja, es grenzt ans Unmögliche. Lieber passt man sich den Folgen der Erwärmung an bzw. betrügt den Partner eben doch wieder heimlich, wie man es immer getan hat…

Der Artikel erschien zuerst bei Sexography, einer englischsprachigen Publikation auf Medium. Ich werde das künftig kenntlich machen.